March 28, 2016

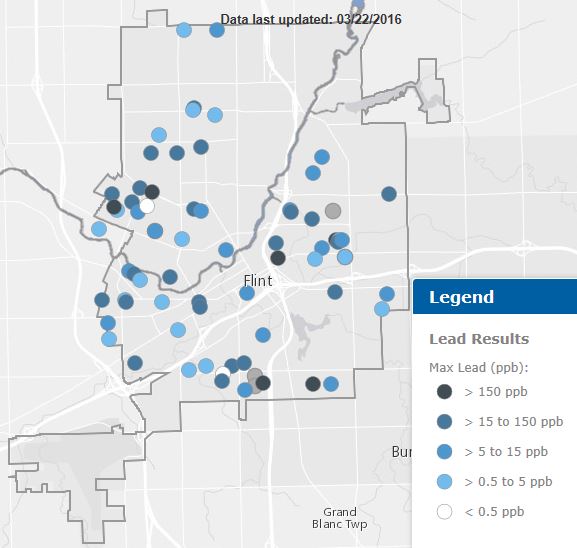

Headlines continue to pour out of Flint since the city’s lead exposure last summer. President Obama’s emergency declaration in January 2016 required federal response to local and state efforts.

How could this happen? Who is accountable? How do we fix it? And what do learn from this tragedy when it comes to engaging vulnerable minority and non-English-speaking communities?

As congressional hearings transpired in mid-March, I reflected on the large-scale response in Flint.

To help residents, the

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is working in with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Small Business Administration (SBA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the departments of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Agriculture (USDA) and Education.

The EPA Region 5 office in Chicago has developed the

Flint Safe Drinking Water Task Force with the National Risk Management Research Lab and is in constant contact with the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality and the Mayor of Flint. A number of nonprofit organizations, as well as state and local government, has also arrived on site to provide relief.

But I continue to wonder: How do we engage communities that are often overlooked in large scale emergency responses? Minorities tend to be the hardest hit and oft forgotten in environmental emergencies, and Flint is no exception.

Before thousands were exposed to lead in their drinking water, 42 percent of Flint’s residents lived in poverty.

Latinos make up just 4% of the population, yet they received less attention compared to the rest of the population. Additionally, 14 percent of Flint residents live without health insurance. How do you reconcile these barriers?

Michigan Radio reported that

undocumented immigrants in Flint continued to drink the contaminated water long after officials advised residents to drink bottled water. According to reports by EPA and Michigan Radio,

Spanish speakers who had been unaware of the contamination began receiving calls from family members in Mexico and South America who had seen reports on CNN en Español and Univision.

Because they hadn’t gotten word of the problem sooner, roughly 1,000 undocumented immigrants did not receive adequate health care or water supplies and continued to drink contaminated water that causes irreversible damage in children.

National Guard Troops, EPA staff, local NGOs, and volunteers found that

many undocumented immigrants were not opening their doors to accept supplies in fear of being discovered. Prior to

a Jan. 22 statement by Michigan state government that lifted the ID requirement to obtain free water supplies,

many were also not going to any of the fire stations or local grocery stores for provisions.

In response to this challenge, NGOs and government agencies began hosting Spanish-language meetings in churches and community schools to reach out to the residents. The EPA published a Spanish-language

website and

documents in order to reach residents, as did

the State of Michigan Governor’s Office. Federal agencies and nonprofit organizations also joined hands to host a public meeting in early March with informational booths to educate residents on lead-poisoning symptoms, filtration systems, and advice.

In addition to the Latino population, the Arab American Heritage Council in Flint reports that many of the 42 Arab-American families also were unaware of the problem. Federal agencies have held informational sessions in Islamic

community centers for Arab-Americans as well. HHS and the Michigan government also published information in

Arabic,

Chinese, and

Spanish.

Leaving public administration best practices and crisis prevention aside, what can we, as current and future public servants, learn from this emergency response? Minority communities are all too often forgotten amid the rubble. It is imperative to seek counsel from community members to find innovative ways to solve problems. In addition to simply engaging these communities, public servants also have the responsibility to reciprocate efforts in the majority communities.

For example,

the

Michigan Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights stated that the organization received reports long after the rule on IDs went into effect that

water distribution centers were asking for IDs

of residents who needed water and supplies. MCIRR pressured the centers to follow regulations when officials should have been enforcing this in the first place. It is the responsibility of nonprofits and governments alike to safeguard citizens’ rights and truly serve the interest of the people. We must be part of the solution.